ADVANCING PEOPLES’ MOVEMENTS FOR JUSTICE,

PEACE, EQUALITY, SUSTAINABILITY AND

DEMOCRACY IN SOUTHEAST ASIA

ACSC/APF 2019 STATEMENT

SEPTEMBER 10-12, 2019

PATHUM THANI, THAILAND

More than 1,000 delegates from eleven Southeast Asian countries gathered in Thammasat University (Rangsit Campus), Pathum Thani, Thailand and discussed the current situation of the region’s societies and their peoples, the various government policies and programs as they impact on vulnerable and marginalized communities and sectors, and drew up recommendations for ASEAN states to act on as well as directions for civil society to take in the coming years.

The situation of Southeast Asian peoples

In Southeast Asia, despite the fact that ASEAN member states have made policy pronouncements on building a “rules-based, people-oriented, people-centered, dynamic, resilient and harmonious ASEAN community” as declared in the ASEAN Community Vision 2025, the association is considered at a crossroads as it enters a new development period characterized by uncertainties, instabilities and high security risks. All these are taking place amidst the US-China economic rivalry which could impact on ASEAN’s political and economic situation.

Politically and strategically, Southeast Asia lies at an important junction, which gives ASEAN a ‘central role” in determining the region’s future while being at the center of competition between the big powers. The South China Sea territorial disputes has long been a critical test for ASEAN, causing strategic trust erosion between some member states.

Power shifts and regime changes in some ASEAN countries have led to the undermining of democratic processes with the rise of authoritarian and right wing populist leaders resulting in widespread violations of human rights including extra judicial killings, forced disappearances, and ethnic cleansing – all contributing to a human crisis in ASEAN. Furthermore, internal conflicts continue to fester such as the Rohingya issue and separatist movements in Southern Thailand and West Papua.

Economically, although ASEAN is a huge market of more than 600 million consumers and is

expected to become the fourth largest economy in the world by 2030, the region is confronted with a variety of challenges, including inequalities within and between countries, poor integration in terms of trade and investment, inefficient economic governance leading to corruption, and pressures by the increase in migrant labor.

On the social and cultural sphere, gender inequalities persevere despite advances in legal initiatives in some countries. Social protection in terms of education, health, housing, living wages, and public services is still inadequate especially for poor and marginalized populations. This is partly due to the widespread privatization of essential services and non-implementation of ILO convention and resolutions protecting worker’s rights. Furthermore, continuing ecological deterioration and severe weather disturbances brought about by climate change as well as the proliferation of large infrastructure and mega development projects have intensified environmental disasters.

ACSC/APF through the years

The ASEAN Civil Society Conference/ASEAN Peoples’ Forum (ACSC/APF) is the Southeast Asian region’s primary network of civil society organizations and peoples’ movements that has been engaging the official ASEAN process since 2005. The sectors represented in ACSC/APF include urban and rural workers in both the formal and informal economy, smallholder farmers, urban poor, fisherfolk, women, sex workers, children, indigenous peoples and ethnic nationalities, local communities, older persons, people living with HIV/AIDS, professionals and rank-and-file employees, children, persons with disabilities, youth, LGBTQI persons, and migrants The multifarious concerns, hopes, and aspirations of these marginalized sectors of Southeast Asian societies form the matrix of ACSC/APF discussions, planning, advocacies, and campaigns.

These concerns include human rights of women, workers, peasants, children, indigenous peoples and ethnic nationalities, and youth; environmental issues (pollution, climate change, and disasters);peace and human security; corporate greed, liberalization, deregulation, privatization and financialization; labor contractualization and resulting precariat work; increasing feminization and vulnerability of informal workers, free trade agreements, militarization, internal conflicts and displacement; migration, trafficking and modern slavery; land issues (land banking, conversions, land grabbing and re-concentration); genuine agrarian reform, food sovereignty, agro-ecology, and agricultural neglect; social protection and the deficit in basic services (health care, education, power and water); gender equality and women empowerment, homophobia, transphobia, misogyny, and the informal sector.

For each of the past thirteen years, ACSC/APF and its member organizations have been holding forums and meetings at the national levels through the country-based National Organizing Committees (NOCs), and regional assemblies including major conferences that parallel the official ASEAN process. In each of these gatherings, ACSC/APF has always endeavored to reach out to ASEAN bodies, mechanisms, and instruments as well as individual governments and bring before them detailed and substantive recommendations for transforming ASEAN into a truly people-centered and people-oriented regional organization.

Peoples’ voices and aspirations are summarized in a final statement meant to inform ACSC/APF’s constituents of the year’s highlights and events that have affected Southeast Asian peoples. It is also intended to be presented to ASEAN governments for serious attention and the proper actions.

ASEAN as a regional organization and its relationship with civil society

Originally formed in 1967 as a political project of five Southeast Asian leaders in the midst of the Cold War, ASEAN has gradually evolved and expanded its scope into a more multifaceted development initiative starting with the 2005 theme of being “people-centered,” later adding “people-oriented.” In 2015, the concept of an ASEAN Community was born revolving around three pillars: Political-Security Community, the Economic Community and the Socio-Cultural Community. Along with other UN member states, ASEAN governments, also endorsed in 2015 the ambitious agenda set out by the sustainable development goals (SDGs), 2016-2030.

However, the coming into being of the ASEAN Community, particularly its economic component, remains a pipedream. The region’s economies compete with rather than complement each other. As a result, economic ties (trade and investments) are stronger with non-ASEAN countries. Politically, the doctrines of “non-interference” and “consensus-building” hamper unified actions, particularly on human rights issues. Most agreements are non-binding and allow each member government to interpret their provisions arbitrarily. ASEAN thus cannot stand as one when confronted by challenges coming from more powerful non-ASEAN states.

CSOs and peoples’ movements, however, have argued that the changes in ASEAN’s perspectives and its pronounced tilt towards prioritizing Southeast Asia peoples’ welfare have been more rhetorical than real. Despite high growth rates, poverty and social inequality remain high. Meaningful peoples’ participation in governmental programs, projects, and decisions are nowhere to be found. Indeed, ASEAN is seen by independent observers as working to preserve and expand the role of traditional political oligarchies and economic corporate elites. As the Ten-Year ACSC/APF Review Report (2005-2015) phrased it: “ASEAN and its member governments have been seen to be more comfortable with the private sector and academic and research think tanks than with civil society.”

As the 2015 and 2017 ACSC/APF statements pointed out:, the development paradigm that guides ASEAN member-states has only bred “greater inequalities, accelerated marginalization and exploitation, inhibit peace, democracy and social progress,” spawned “economic, social, and environmental crises, extensive human rights violations, situations of conflict and violence, and wanton exploitation of natural resources that are overwhelming the region’s ecosystems.”

Despite an explicit recognition by ASEAN of the role that CSOs can perform in its three pillars, and the recognition of the ACSC/APF as the formal platform for CSOs, the thirteen-year engagement by CSOs with the official ASEAN process has hardly borne fruit. For one, ASEAN defines a CSO in a self-serving manner as “a non-profit organisation of ASEAN entities, natural or juridical, that promotes, strengthens and helps realize the aims and objectives of the ASEAN Community and its three Pillars …”

In other words, “ASEAN’s preference appears to be for a civil society that will help it achieve the already established goals and projects of ASEAN’s governing elite rather than a civil society that will — through genuine, two-way deliberations — help ASEAN set these goals and agendas in the first place.”

Not surprisingly, the Ten-Year Review Report concluded that “individual ASEAN member countries have consistently resisted and vacillated with regards civil society participation and engagement” and that “high expectations for people‘s participation in ASEAN, encouraged by the promise of a ‘people-oriented ASEAN’… are thus not met, leading to frustration amongst those in civil society who have chosen to engage ASEAN at various levels.”

ACSC/APF 2019 – issues and recommendations

All four ACSC/APF 2019 plenary sessions raised the issue of democracy and its status as a key concern. The suppression, arrests and prosecution of activists critical of governments have continued unabated. The Southeast Asian region has been confronted by issues on security, justice, ecological destruction and assaults on human rights. Deteriorating democratic institutions threaten individual security without which there can be no national security. Moreover, many Southeast Asian peoples are losing their lands and livelihood due to mega projects which also impact on the environment. Indigenous peoples and ethnic nationalities who have long lived and relied on nature are now illegal in their own land.

To achieve sustainable and equitable development, equal partnership must be forged between governments, peoples’ organizations, civil society groups, and all stakeholders. Affordable and accessible health care for everyone and protection of the rights of persons with disabilities, which are enshrined in constitutions and laws in ASEAN member countries, can only be delivered within the context of strong commitment by governments and service providers.

There is a widening gap between the poor on one hand, and the rich and propertied on the other resulting in economic disparities and social inequalities in various dimensions. Southeast Asia peoples must build alternatives based on the peoples' fundamental right to live with dignity and resist policies which favor and privilege only investors and corporate interests.

The seven convergence spaces under ACSC/APF 2019 are (1) peace and security, (2) human rights, democracy and access to justice, (3) trade, investment and corporate power, (4) ecological sustainability, (5) innovation, new, and emerging technologies and digital rights, (6) migration, and (7) life with dignity (decent work, health and social protection). Several workshops under the seven convergence spaces discussed and adopted the following analyses and recommendations:

I. Peace and Security

Southeast Asia continues to be challenged by critical security issues such as terrorism, piracy, cross border crimes, drug and human trafficking, smuggling, migration crisis, natural disasters, climate change, and the rise of authoritarian leaders. Moreover, in the context of a rapidly changing world, the region is caught between the strategic competition between major powers, undermining efforts at unity and solidarity within ASEAN. The US, for one, has long been engaging actively in the region through its military presence and economic agenda while China is using both financial tools and military power to expand its territorial claims, especially in resource-rich marine areas. Conflicts between ASEAN states also exist particularly trade disputes, conflicting territorial claims, the treatment of migrant workers and cross-border pollution. All these threaten regional peace and human security and peoples’ livelihoods.

Recommendations to ASEAN governments:

Synergize ACWC and AICHR by strengthening their mandates and functions and create regional mechanisms for reporting and resolving human right violations including and gender-based violence;

Engage people from all walks of life, including women in solving peace and security-related problems and fully achieve the SDGs;

Push for the settlement of disputes by peaceful means, in the spirit of solidarity and respect for international law; develop an alternative approach committed to multilateralism, a shared regional identity and people-to-people concerns; and,

Hold developed countries accountable on the effects of climate change and toxic waste disposal.

II. Human Rights, Democracy and Access to Justice

Urban and rural workers, smallholder farmers, urban poor, fisherfolk, women, children, indigenous peoples and ethnic nationalities, older persons, professionals and rank-and-file employees, persons with disabilities, youth, LGBTIQ persons, human rights defenders, and migrants suffer exclusion from the mainstream of social, economic, and political aspects of Southeast Asian societies and communities. ASEAN member states, either by indifference or by deliberate effort, have allowed LGBTIQ persons to be targeted as threats to national security and public morality.

ACSC/APF deplores the rise of authoritarian regimes, the shrinking civic space in the region, and the ineffectiveness and inaction of AICHR in addressing human rights issues of Southeast Asian peoples. Commissioners are appointed in a non-democratic manner while civil society groups face difficulties in engaging with AICHR officials and representatives.

Recommendations to ASEAN governments:

Ratify the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearances (CED) and recognize that enforced disappearances are a crime against humanity;

Support and assist independent human rights investigations and international fact-finding missions in countries or areas of critical circumstance;

Establish new human rights architecture/bodies and transform AICHR from an intergovernmental commission to an independent and autonomous body and strengthen its mandate for information gathering/fact finding and providing justice for victims;

End all forms of militarism and the misuse of emergency laws and security related legislation;

Respect the fundamental rights of peoples including freedom of expression, association and assembly, release all political prisoners/detainees and drop all charges against dissident voices;

Promote, enhance, formalize, respect, and trust human rights defenders especially the youth and enable their participation in all decision-making processes;

Affirm the civil and human rights of LGBTIQ persons in accordance with international human rights standards; and,

Review and revise the ASEAN Charter particularly on providing spaces for CSOs to engage fully at the policy and implementation levels.

III. Trade, Investment and Corporate Power

ASEAN governments continue to push for a corporate-driven development framework/paradigm that has worsened poverty and inequality, undermined peoples’ rights, intensified vulnerabilities, and destroyed fragile ecosystems. Trade and investments continue to be the main drivers of economic growth and development in Southeast Asia. Governments have defaulted on their responsibility for economic development in favor of corporations, prioritized investor protection while weakening regulation, and continue to push for unjust international trade and investment agreements such as the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (RCEP).

The expansion of special economic zones, capitalist ocean grabbing, and mega infrastructure projects have displaced and marginalized communities of farmers, fishers, rural women, and indigenous peoples and ethnic nationalities. There is also an alarming rise in extra-judicial killings of environmental, land and human rights defenders.

But peoples’ resistance to the above developments continues and is intensifying. The building of alternatives is also underway anchored on various community-based initiatives.

Recommendations to ASEAN governments:

Stop corporate attacks on workers, farmers, indigenous peoples and ethnic nationalities and local communities, and hold governments and corporations accountable amid prevailing investment liberalization and the corporate capture of the sustainable development agenda driven by international finance institutions;

Put in place stronger and more effective regulations that curb the power of corporations and are anchored on protecting people’s rights and promoting peoples’ welfare;

Reject RCEP and other new generation free trade agreements, and initiate processes to review existing trade and investment agreements; and,

Support the process towards a legally binding instrument on TNCs and human rights at the United Nations Human Rights Council and support other such mechanisms to exact accountability of corporations for human rights abuses and provide effective remedies and access to justice.

IV. Ecological Sustainability

Southeast Asia is facing multiple environmental crises. Lands, forests, rivers, biodiversity, water and air quality, which are critical to people’s well-being and sustainable development, are being polluted, degraded and destroyed. Climate change is exacerbating these impacts, undermining people’s resilience and increasing displacement. The prioritization of economic interests and corporate profits are marginalizing environmental concerns and crippling people’s rights. A people-centered ASEAN, which is just, prosperous, and genuinely sustainable, cannot be achieved unless the roles, rights and livelihoods of people are respected and upheld.

Recommendations to ASEAN governments:

● Launch a fourth strategic pillar on the environment, to put international best practices and

environmental sustainability at the center of decision-making;

● Ensure transparency and public participation in environmental decision-making. Establish an open access e-data platform on development, infrastructure, energy and land projects including project information and impact assessments to outline both trans-boundary and accumulative impacts;

● Ensure and guarantee genuine free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) of indigenous peoples and ethnic nationalities in development projects and promote best practices for implementing FPIC by corporate actors.

● Strengthen and enforce legal regimes to monitor and punish environmental polluters;

● Prioritize energy policies and plans that ensure just energy transitions that maintain the integrity of ecosystems and respect the rights and well-being of people;

● Promote allocation of resources to support people in creating and developing environmentally sound social innovations and people-centered markets, trade and investment; and,

● Recognize local communities’ rights over their land and resources. Ensure their rightful participation in all development decisions affecting their lands, life and survival, environment and future.

V. Innovation, New and Emerging Technologies and Digital Rights

New and emerging technologies promoted to address climate, food and environment crises and raise productivity and efficiency are mostly developed and controlled by corporate interests, making it inaccessible to local communities and detached from the needs and realities of Southeast Asian peoples. Corporate digital platforms are being run without meaningful peoples’ participation in governance; and data are being collected without informed consent and mainly for profit.

Recommendations to ASEAN governments:

Channel resources, support, and upscale participatory, transparent and democratic governance of technologies, ensure peoples’ ownership and control of their data, and evaluate the potential impacts on human health, society, livelihood and the environment prior to technological deployments;

Uphold and integrate people’s digital rights in the ASEAN digital masterplan, on cybersecurity cooperation, and data protection and privacy; and,

Immediately stop prosecuting and drop all pending charges against activist filmmakers and journalists for posting content, videos, and photos on social media.

VI. Migration

Despite the 2018 adoption of the ASEAN Consensus on the Protection and Promotion of the Rights of Migrant Workers, the framework, documentation and nationality of migrant workers and their family members remain the main challenges for upholding migrants’ human rights and fundamental freedoms on citizenship, fair wages, affordable working permits, simple application processes, debt bondage, and social protection issues including health, trafficking, abuses and modern slavery.

Recommendations to ASEAN governments:

Promote and protect human rights of migrants by strengthening existing mechanisms for both documented and undocumented workers and their families;

Undertake effective consultation and collaboration with civil society and trade unions in the implementation of the ASEAN Consensus on the Protection and Promotion of Migrant Workers;

Protect the rights of refugees and asylum seekers, including preventing their forcible return to a country where they face prosecution (non-refoulement) and advance progress across the region on refugee legal status, work rights, and access to education and health care; and, Recognize and address the vulnerability of stateless people, especially girl-children, by establishing a single protocol and standard in defining legal identity.

VII. Life with Dignity (decent work, health and social protections)

Most people in Southeast Asia continue to experience poverty, vulnerability, and inequalities. Majority of the work force, including migrant workers, are engaged in the precarious informal economy. Non-adoption and implementation of the ILO Core Labor Standards, and lack of rights awareness have aggravated workers’ conditions. Social protection to address inequalities and ensure vulnerable groups from falling into poverty have remained limited and largely temporary. The social dimension is clearly missing in ASEAN. But there exist alternative development practices by and among peoples that may

be promoted as alternatives to ASEAN’s business-oriented economic integration.

Recommendations to ASEAN governments:

Legislate and implement a rights-based and inclusive social protection framework, policies, and processes, ensure living wage and income for all;

Ratify and implement the ILO core labor standards essential to creating conditions to achieve decent work, guarantee universal healthcare for all, and end efforts at privatizing health and other public services;

Commit to dialogues, collaborate and share knowledge and resources towards advancing a common agenda to realize a life of dignity for all with people’s movements, trade unions, NGOs, parliamentarians, and academe;

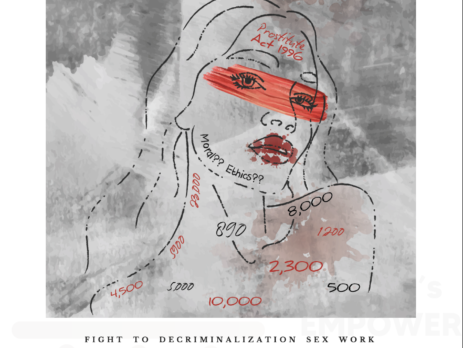

Recognize sex work as work and repeal laws and rescind policies that criminalize and stigmatize sex workers and violate their rights; and,

Commit to the ILO-recommended 6% international minimum standard country budget allocation for social protection and continue to increase the fiscal space for universal social protection.

Future directions and alternatives for ACSC/APF

In order to build a stronger network of Southeast Asian peoples supported by civil society

organizations, social movements and people’s organizations, ACSC/APF will undertake the following:

Intensify engagements with and hold governments accountable on human rights, peace and security, trade and investment, ecological sustainability; new and emerging technologies and digital rights; migration; decent work, health and social protection, and other critical issues;

Continue to disseminate and demand meaningful responses from ASEAN leaders and

governments on the three major CSO statements on social protection, decent work and social services and the ACSC/APF proposed framework for an ASEAN-civil society dialogue on environment that recommends a fourth strategic pillar on the environment;

Strengthen assertions by civil society and people’s movements of the people’s right to determine their development path and enjoy the outcomes of community-driven development;

Emphasize activities and campaigns in public places related to peoples’ culture and art through various cultural forms and platforms;

Create a platform for the engagement of younger generation of activists and human rights

defenders in order to promote their full and meaningful participation in all decision-making

processes;

Broaden alliances by civil society and people’s movements and intensify advocacies and

campaigns against unjust trade agreements such as RCEP and expose their negative impacts on peoples and communities;

Recognize and support social and solidarity economy initiatives of the people as countervailing alternatives to global neoliberal capitalism, and as integral components of a people-oriented Southeast Asian regional integration;

Continue to monitor the process of Timor Leste's accession into full ASEAN membership. In solidarity with the people of Timor Leste, we take the principled view that ASEAN membership must not be accompanied by corporate or foreign plunder of its natural resources or endanger its people's rights; and,

Finally, given that years of ACSC/APF engagement with the official ASEAN process have been met with lack of attention to the recommendations raised, resulting “in minimal outcomes in the substantive improvement in the lives of our people,” undertake a process for an alternative peoples’ regional integration based on the alternative practices of communities, sectors, and networks. Accordingly, ACSC/APF will adopt the appropriate resolution related to the proposed process.

Through all these years, Southeast Asian peoples have been subjected to all forms of indignities and oppression that have made lives untenable for the great majority. The transformation of these conditions for the better is long overdue. Civil society organizations and peoples’ movements must persist in advocating peoples’ and grassroots’ voices and interests and in pursuing greater popular participation in decision making on policies, programs, and projects.