The workforce of the world is the foundation of the economy and thus stimulates growth and sustainability on the planet. Even if going on with the economic transactions on a surface level, there are still several dynamics hidden in the mechanism that affect the labor class and social welfare. Here is the exploration of the complicated nature of labor practices in which the interplay of corruption and power dynamics play a pivotal role. Corruption that ranges from bribery to its extreme version is known as exploitation and manipulation. Similarly, the imbalanced power distribution of workers exacerbates the gaps, which is maintained by this cycle of injustice, which itself undermines workers’ basic rights and dignity. This article aims to study and understand the process of marginalization of labor in Thailand and how it is linked to corruption system. This study was merely conducted by studying on other research from academics and international organization reports.

The content will be following:

- The History and Development of the Labour Force in Thailand

- The Characteristics of Thailand’s Labour Market

- The Labour Activism in Thailand

- Corruption and Exploitation in the Labour Sector

The Development of the Labour Force in Thailand

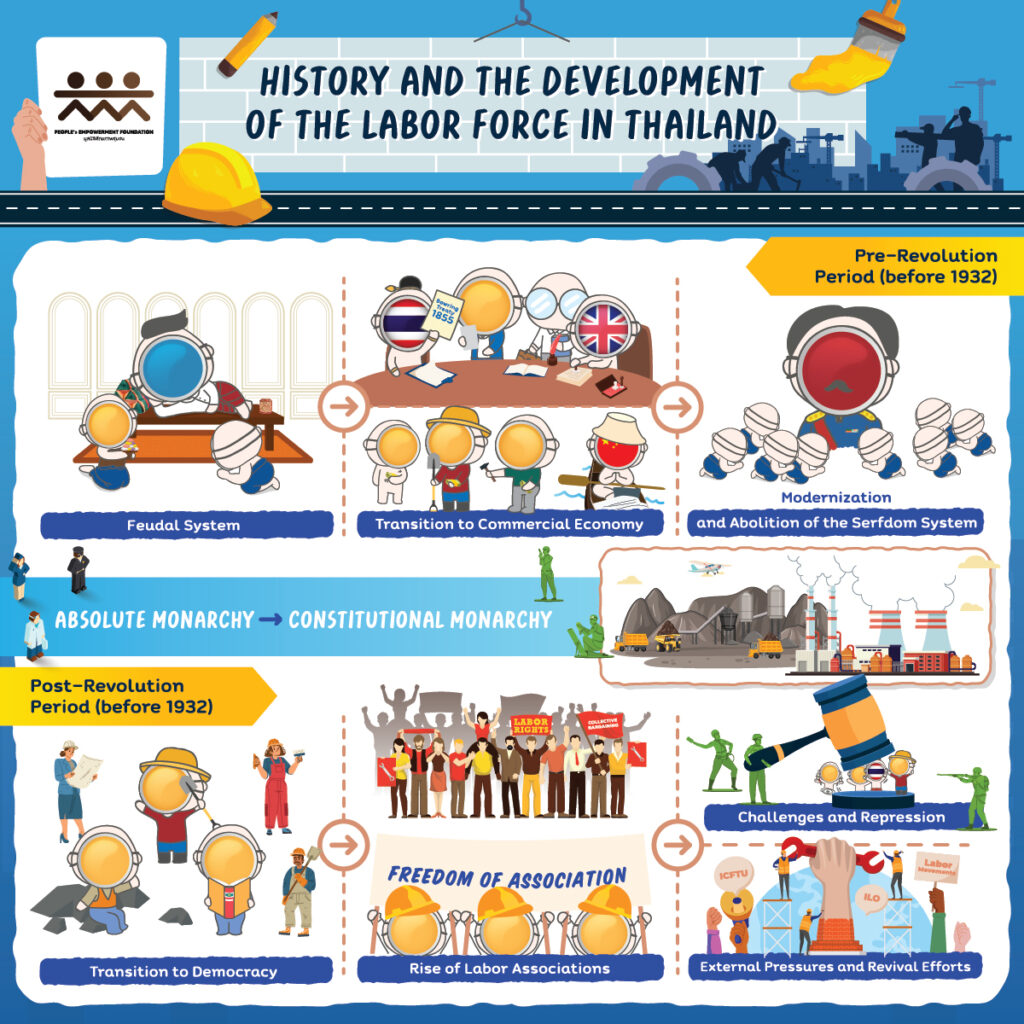

the development of the labor market in Thailand can be divided into two distinctive periods: pre-revolution (before 1932) and post-revolution (after 1932).

Pre-Revolution Period (Before 1932)

- Feudal Labor System: Thailand operated under a feudal system characterized by a hierarchical social structure. At the top were the King and feudal officials, while serfs and slaves comprised the bottom layer. Serfs and slaves were subjected to forced labor without compensation, primarily in agriculture, construction, and defense.

- Transition to Commercial Economy: The signing of the Bowring Treaty in 1855 marked Thailand’s transition from a feudal to a commercial economy. This shift created a demand for paid labor, leading to the influx of migrant workers from China to fulfill labor needs in emerging industries and infrastructure projects.

- Modernization Initiatives: Under King Rama V, Thailand embarked on modernization initiatives, including the abolition of the serfdom system. This transitioned many Thais from agrarian self-sufficiency to wage labor in emerging industries like rubber processing, mining, and forestry.

Post-Revolution Period (After 1932)

- Transition to Democracy: The revolution of 1932 ushered in a transition from absolute monarchy to constitutional monarchy and paved the way for democratic reforms. This period saw increased political freedoms and the emergence of collective labor action.

- Rise of Labor Associations: Economic recessions and political liberalization contributed to the rise of labor associations and collective bargaining. Workers in various sectors, such as tram, cement plant, and train workers, formed associations to advocate for labor rights and fair treatment.

- Challenges and Repression: Despite gains in collective bargaining, labor movements faced challenges and repression, particularly during military-led governments. The Thai government suppressed labor movements perceived as threats to stability, using legislation and force to curb dissent.

- External Pressures and Revival Efforts: External pressure from international labor organizations, such as the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions (ICFTU), influenced labor rights advocacy in Thailand. Efforts to revive labor parties and movements persist, but political involvement remains limited, reflecting ongoing struggles within Thailand’s labor sector.

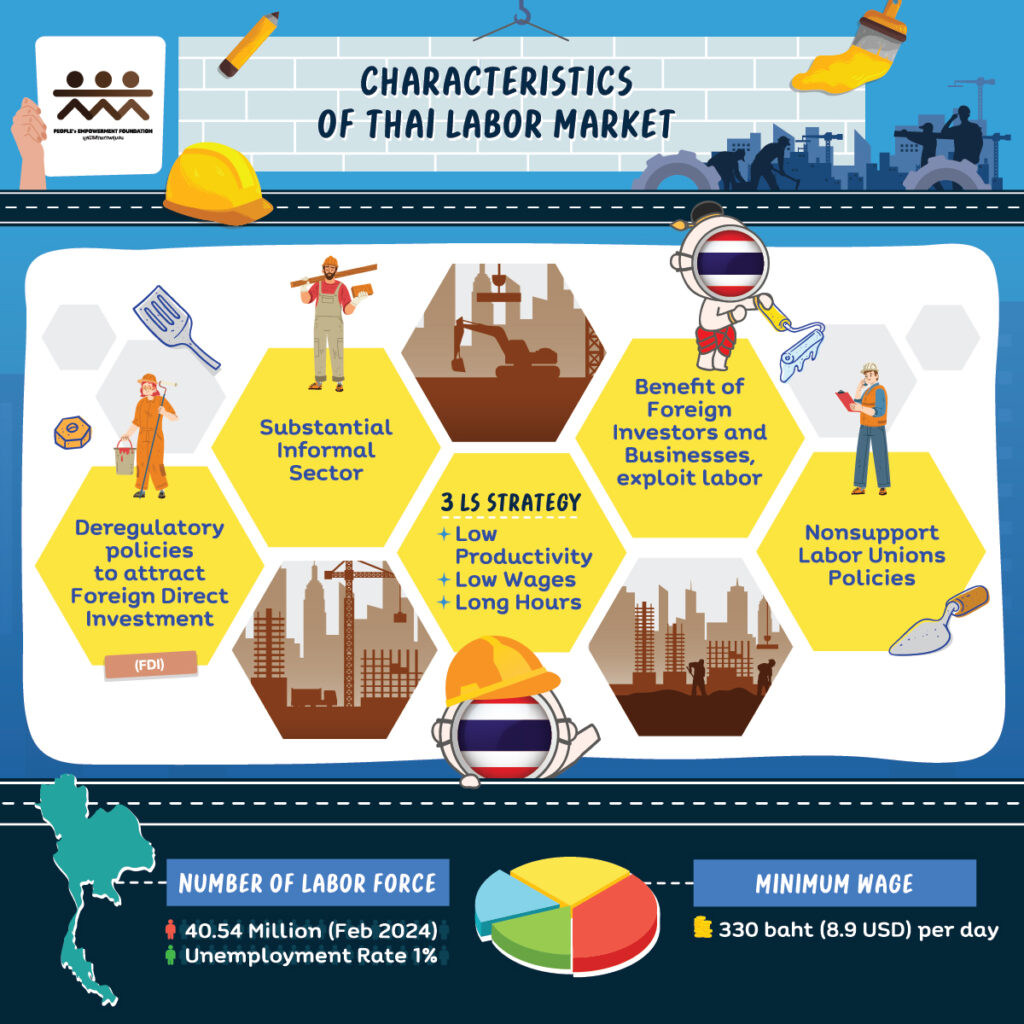

As a developing country, Thailand’s labor market is characterized by a substantial informal sector, which may serve as a transitional space for individuals entering formal employment. Thailand’s labour market policy, rooted in the East Asian Economic Model (EAEM) since the 1950s, prioritizes export-oriented low-cost manufacturing and fosters a favorable investment climate for both foreign and domestic investors. This approach relies on maintaining low wage costs, facilitated by a large pool of under-employed agricultural labor and limited labor rights, including suppressed trade unions and restricted freedom of association and speech. The Board of Investment (BOI) plays a central role in attracting foreign investment through incentives such as tax breaks and access to infrastructure, particularly in designated industrial estates.

However, the efficacy of these incentives in stimulating genuine investment rather than diversion remains questionable, potentially distorting markets and perpetuating marginally profitable activities. The prevalent 3Ls strategy—low productivity, low wages, and long hours—characterizes the labor landscape, with generations of factory workers engaged in repetitive tasks for the benefit of foreign investors.

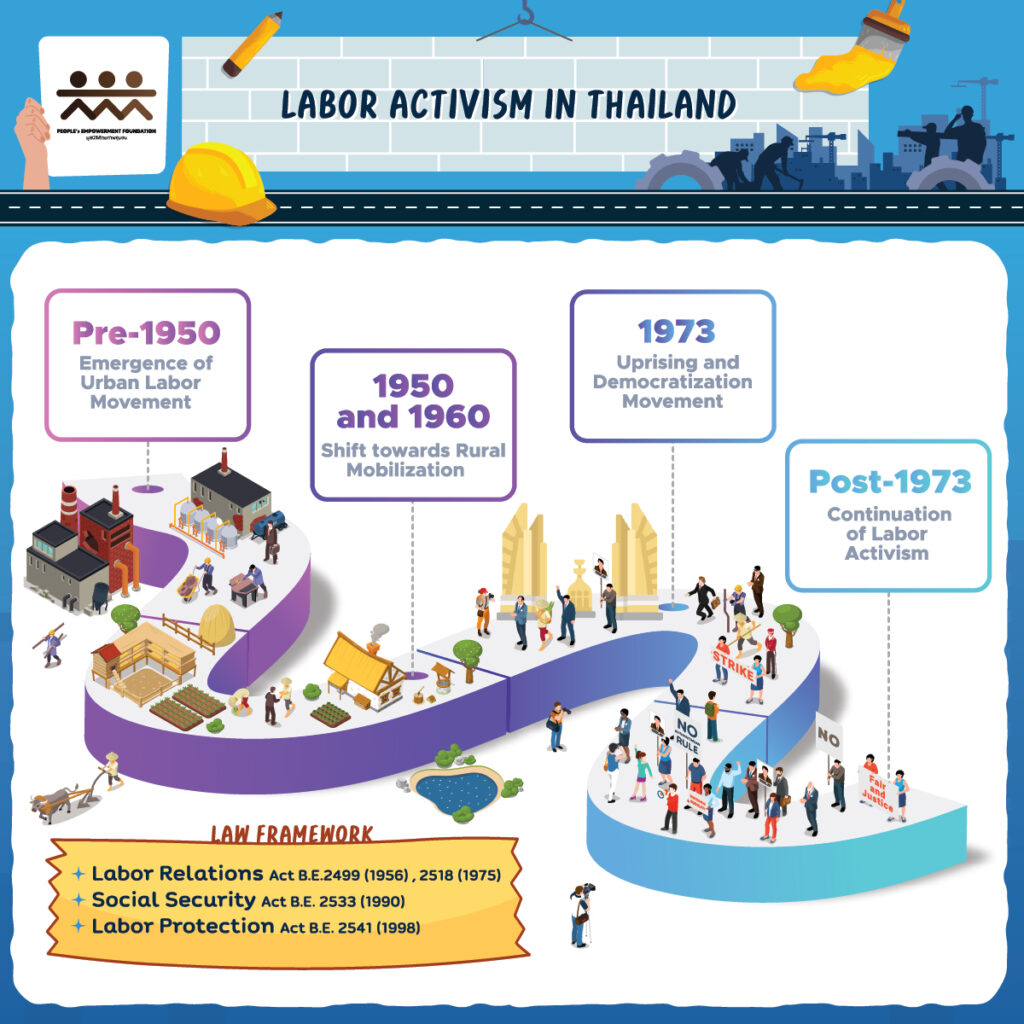

The evolution of Thailand’s labor force has been closely intertwined with the tireless advocacy of labor activists throughout the nation’s history. As Thailand transitioned from a feudal society to a modernizing economy, labor activists emerged to challenge exploitative labor practices and fight for the rights of workers. Despite facing considerable obstacles, including repression from authoritarian regimes, these activists persisted in their efforts to improve working conditions, secure fair wages, and protect the interests of the labor force. Their activism has been instrumental in driving legislative reforms, promoting collective bargaining, and fostering a culture of worker solidarity. Over time, labor activists have become integral figures in shaping Thailand’s labor landscape, advocating for social justice and empowering workers to assert their rights in the face of adversity. Their unwavering dedication underscores the enduring link between the development of the labor force and the resilience of labor activism in Thailand.

The history of labor activism in Thailand is a rich tapestry woven with the threads of struggle, resistance, and resilience. From the early urban labor movements of the pre-1950s era to the rural mobilization efforts of the mid-20th century and the pivotal role of workers in democratic uprisings, the labor force in Thailand has left an indelible mark on the country’s socio-political landscape.

- Pre-1950s: Emergence of Urban Labor Movements

Before the 1950s, labor activism in Thailand was predominantly urban-centric, with early signs of organized movements influenced by the operations of the Communist Party among workers in Bangkok. The victory of the Communist Party in China prompted strategic shifts within the Thai Communist Party, redirecting its focus towards mobilizing rural peasants and laying the groundwork for broader social movements. This period laid the foundation for future labor mobilization efforts. (Ungpakorn, 1995; Poonpanich, 1988)

- 1950s and 1960s: Shift towards Rural Mobilization

The subsequent decades witnessed a notable shift towards rural mobilization, spurred by political repression under successive governments. The Communist Party prioritized armed struggle among peasants, expanding labor activism beyond urban centers and drawing rural communities into political and social struggles. This period marked a significant expansion of the labor movement’s reach and influence across the country. (Ungpakorn, 1995)

- 1973: Urban Uprising and Democratization Movement

The year 1973 marked a watershed moment in Thailand’s history with the urban uprising and democratization movement. Fueled by widespread social discontent, workers played a central role in strikes and demonstrations, demanding political reforms and challenging authoritarian rule. The uprising led to significant political changes and underscored the power of collective action in shaping Thailand’s political landscape. (Ungpakorn, 1995)

- Post-1973: Continuation of Labor Activism

In the aftermath of the 1973 uprising, labor activism remained a potent force in Thai society. Workers continued to engage in strikes and collective action to address issues of exploitation and injustice, advocating for labor rights and challenging the status quo. The May Uprising of 1992 further exemplified the enduring role of the working class in mobilizing against authoritarian rule and economic inequality, highlighting their resilience and commitment to political change. (Ungpakorn, 1995)

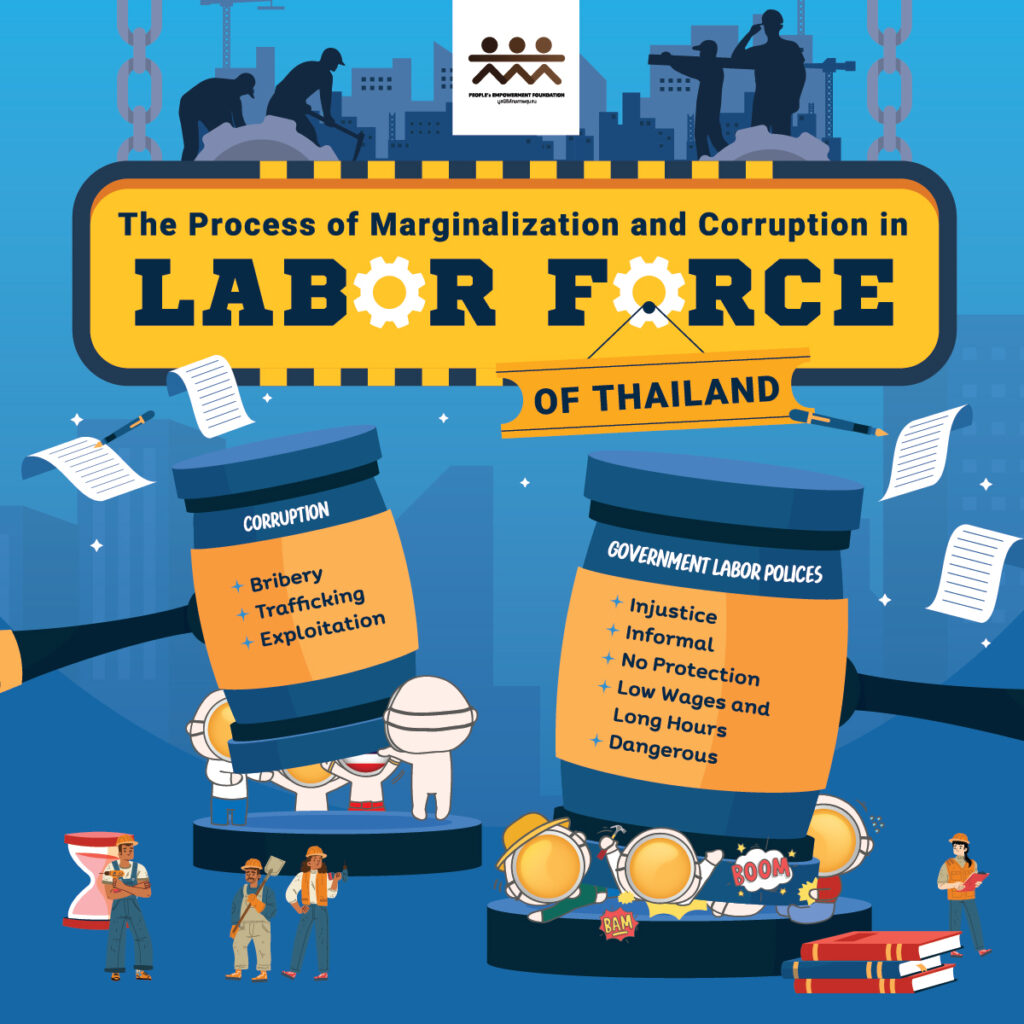

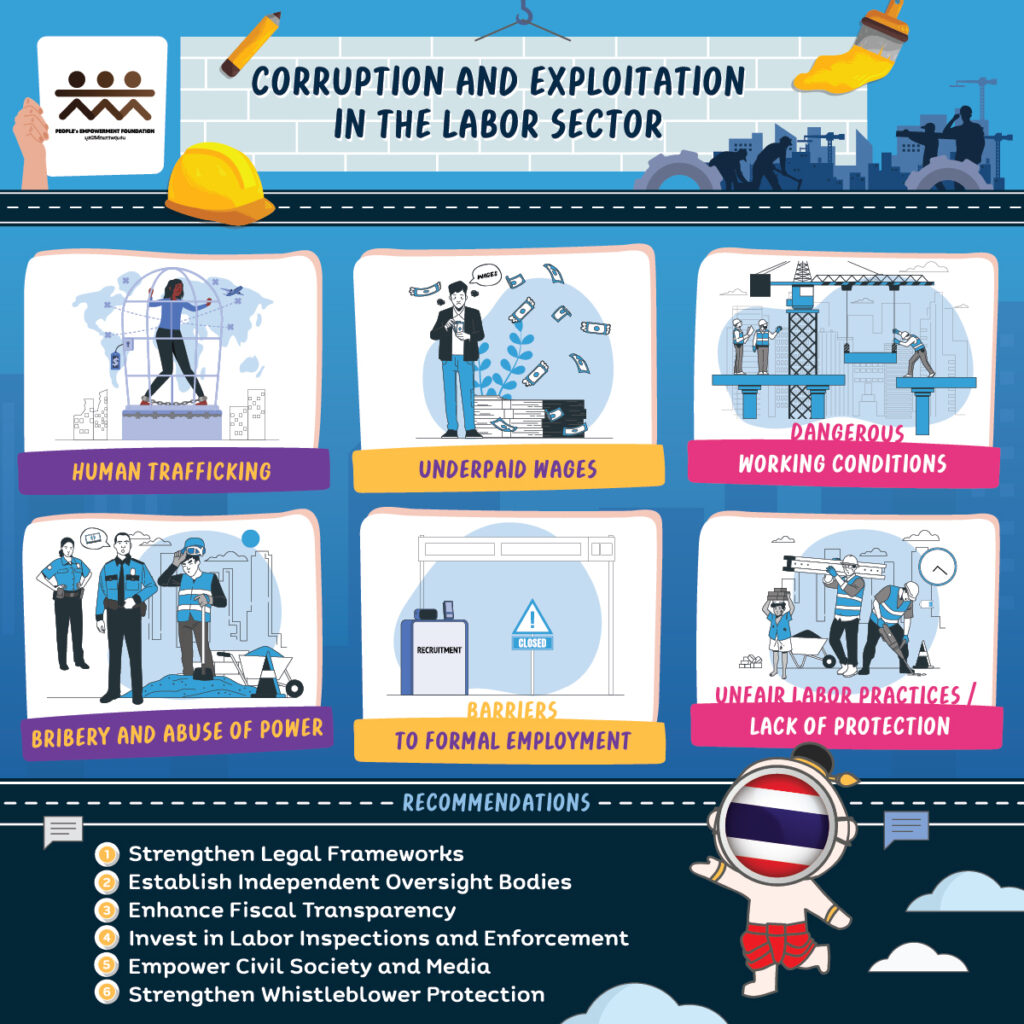

The detailed examination of corruption and exploitation within Thailand’s labor sector, as elucidated in the provided information, resonates strongly with the findings of Walsh’s study on labor market and corruption issues in Chiang Rai, Thailand (2010), published in the Review of Economic and Business Studies (REBS) (Vol. 6, pp. 253-268). Walsh’s study underscores how corruption permeates various facets of the labor market, leading to systemic issues such as human trafficking, underpayment of wages, and dangerous working conditions.

Moreover, Walsh’s analysis resonates with the broader socio-economic context outlined in the provided information, highlighting the historical and cultural factors that contribute to the perpetuation of corruption and exploitation in Thailand. Through empirical evidence and theoretical insights, Walsh underscores the detrimental impact of corruption on workers’ rights and economic development in Chiang Rai and beyond. Additionally, Walsh’s examination of corrupt union officials aligns with the concerns raised regarding the abuse of power within labor organizations, further emphasizing the need for systemic reforms to combat corruption and uphold labor standards.

Within this context, Cooray and Dzhumashev’s study (2018) sheds further light on the detrimental influence of corruption on labor market dynamics, aligning with the observations made by Walsh and corroborating the widespread nature of corruption within Thailand’s labor sector. Corruption undermines labor market efficiency by distorting recruitment processes, fostering unfair labor practices, and creating barriers to formal employment opportunities, as highlighted by the International Labour Organization: ILO (2015) among others. This resonates with the challenges faced by workers in Thailand, where corruption permeates various aspects of the labor sector, from recruitment processes to workplace conditions.

Concrete examples further illustrate corruption’s pervasive impact on Thailand’s labor sector, notably through large-scale infrastructure projects tainted by allegations of graft. The Suvarnabhumi International Airport project stands out as a glaring example, marred by corruption allegations from its inception (Ouyyanont, 2015). Similarly, the abandoned pillars of the Hopewell Rail project serve as haunting reminders of corruption’s enduring legacy, collapsing under the weight of corruption and incompetence (Braun, 2010). These instances underscore the urgent need for comprehensive anti-corruption measures to protect the rights and dignity of workers in Thailand.

Recommendations for further solutions

- Strengthen Legal Frameworks:

- Establish Independent Oversight Bodies

- Enhance Fiscal Transparency

- Invest in Labor Inspections and Enforcement

- Empower Civil Society and Media

- Strengthen Whistleblower Protection